You can respond to the unpredictability of AI coding tools by focusing on their output or input.

- On the output side, you can emphasize code review and write comprehensive tests.

- On the input side, you have the idea of prompt engineering, “the process of writing effective instructions for a model, such that it consistently generates content that meets your requirements.”

Spec-Driven Development (SDD) is a kind of prompt engineering. At a basic level, the idea is to write detailed specifications for a complex change you want the AI to make. You play product manager, AI plays engineer. And like AI can help you write tests, AI can help you write specs.

Definition and Philosophy

This Fowler article defines SDD in light of various usages of the term.

Spec-driven development means writing a “spec” before writing code with AI (“documentation first”). The spec becomes the source of truth for the human and the AI.

After looking over the usages of the term, and some of the tools that claim to be implementing SDD, it seems to me that in reality, there are multiple implementation levels to it.

Spec-first: A well thought-out spec is written first, and then used in the AI-assisted development workflow for the task at hand.

Spec-anchored: The spec is kept even after the task is complete, to continue using it for evolution and maintenance of the respective feature.

Spec-as-source: The spec is the main source file over time, and only the spec is edited by the human, the human never touches the code.

All SDD approaches and definitions I’ve found are spec-first, but not all strive to be spec-anchored or spec-as-source. And often it’s left vague or totally open what the spec maintenance strategy over time is meant to be.

Spec-kit

That last point was clear to me when evaluating GitHub’s spec-kit. Spec-kit provides commands for your AI tool that help you generate planning documents:

constitution.md, an overall philosophy and guidelines for your projectspec.md, laying out user stories for a feature- Various planning documents for the feature that focus on implementation (

research.md,data-model.md,quickstart.md, which can already include code) tasks.md, splitting out concrete tasks from the planning documents, putting them in order and identifying what can be done in parallel.

Once these documents are generated, spec-kit provides an /implement command to use them to implement the feature. But then, what happens to these documents after the feature is developed?

- Are they meant to be frozen, a representation of the feature at the time of implementation? If so, how useful is that as future features change the code. This might best be treated as a kind of changelog.

- Are they meant to be edited as a feature changes, serving as a living representation of the feature? If we need to make a change to a feature, do we edit its spec as we edit its code? This would be the spec-anchored approach—and spec-as-source if the human never touches the code; i.e., instead of changing the code and updating the spec, we update the spec, and tell the AI to change the code.

The “spec driven” manifesto-like document (which reads like it was written by AI) insists that specifications are the source of truth, and the code is simply generated from it.

The gap between specification and implementation has plagued software development since its inception. We've tried to bridge it with better documentation, more detailed requirements, stricter processes. These approaches fail because they accept the gap as inevitable. They try to narrow it but never eliminate it. SDD eliminates the gap by making specifications and their concrete implementation plans born from the specification executable. When specifications and implementation plans generate code, there is no gap—only transformation.

Specifications as the Lingua Franca: The specification becomes the primary artifact. Code becomes its expression in a particular language and framework. Maintaining software means evolving specifications.

This would seem to lead to the approach that you edit an existing specification and then update the code by generating from that, allowing the spec to be the source of truth for your app. But instead, spec-kit leads you to create a new feature spec for every change. In that paradigm, the specs are a source of truth in the sense that they’re a changelog—you need to read/run them one after another to compile the current state.

This discussion raises many of the conceptual and practical pain-points of spec-kit, including the issue of not having a “master spec” that maintains the current state of the application.

What is missing is a snapshot of the project specification on the memory folder, alongside with the constitution. This master spec should be updated when a feature is complete. I think you can even ask the AI to do that and review the output. This master spec should be the starting point for the next feature.

I agre, there should always be a single, consolidated specification that reflects the most current features. Without this, it’s inevitable that, over time, the model could accidentally reference outdated information.

Whenever a feature is updated, the root specification should be updated as well. This ensures there’s always a reliable, up-to-date source. If the specification grows too large, there should also be a logical way to reorganize or structure it for easier navigation.

Yes I agree. I do think we need a master spec. The truth of the system being a chain of specs is horrible for humans and probably inefficient for AI. Obviously we can get it to generate that ourselves, but it being the final step in the spec kit flow would be nice.

There was a comment there suggesting that spec-kit already tries to do this if you have e.g. a GEMINI.md file, and a comment from the creator approving the idea of spec-kit updating the spec. So it seems like a “master spec” completes spec-kit’s idea of “spec-as-source”. You make changes to the code through feature specs, and you maintain a natural-language representation of the code with a master spec. You do not make changes to the code independent of a feature spec, and you do not edit a feature spec.

Kiro

In Kiro, you do edit feature specs when you make changes, making them a living representation of that feature.

Kiro's specifications are designed for continuous refinement, allowing you to update and enhance them as your project evolves. This iterative approach ensures that specifications remain synchronized with changing requirements and technical designs, providing a reliable foundation for development.

- Update Requirements: Either modify the

requirements.mdfile directly or initiate a spec session and instruct Kiro to add new requirements or design elements.- Update Design: Navigate to the

design.mdfile for your spec and select Refine. This action will update both the design documentation and the associated task list to reflect your modified requirements.- Update tasks: Navigate to the

tasks.mdfile and choose Update tasks. This will create new tasks that map to the new requirements.

In other words, Kiro is also spec-as-source, and the specs function as evolving specifications, not as a changelog.

Kiro has a lighter approach to spec-driven development than spec-kit, with requirements.md→ design.md → tasks.md.

requirements.mduses EARS (Easy Approach to Requirements Syntax), which is similar to spec-kit’s user stories.WHEN a user submits a form with invalid data THE SYSTEM SHALL display validation errors next to the relevant fields

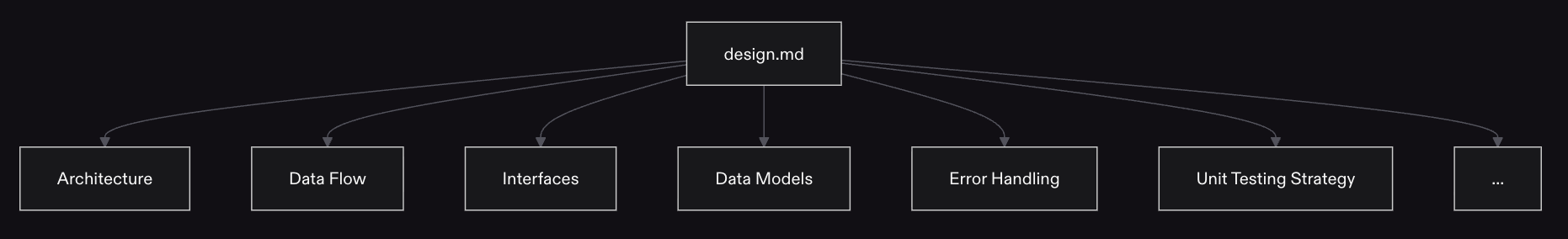

- The design phase is equivalent to

spec-kit’s plan phase, anddesign.mdhas many of the elements of spec-kit’s disparate planning docs. “The design.md file is a great place to capture the big picture of how the system will work, including the components and their interactions.” tasks.mdlists tasks with references to tasks they’re dependent on

Claude Code’s Plan Mode

Claude Code’s plan mode is a light alternative to spec-driven development. It’s unopinionated and can be used to piece together your own workflow. Plan mode isn’t a hardcoded functionality; it’s actually a custom prompt that tells Claude to examine your codebase, ask you questions, and not to edit any code. It walks you through creating a “plan”, which is formulated like a long prompt, not a spec document driven by requirements or user stories. By default, the plan is not added to your project’s repository—they are stored in the .claude/plans/ directory within your home folder.

You can customize any of this behavior by editing your memory/CLAUDE.md file (open it with /memory). So you could borrow aspects of spec-driven development (for example, EARS formatting for feature descriptions, or interactive questioning like spec-kit’s clarify) and bring them to Claude Code’s plan mode.

You can tell Claude to make a plan multiphase, splitting an intensive plan into phases, giving you stopping points to clear Claude for fresh context. You’ll need to bring the plan over to your new context. You can have Claude save the plan to your project, as spec-kit and Kiro would do. In this video, Matt Pocock tells Claude to upload the plan as a GitHub issue. He has it create checkboxes, similar to spec-kit and Kiro, so it can track its progress. Once the context is clear, he tells Claude to get the issue and continue.

I view plan mode as a flexible tool that can be used to implement spec-driven development. At minimum, plan mode is spec-first. If you keep the documents around and use them for later reference, it can be spec-anchored. And if the only way you write code is by iterating on and then implementing these plan documents, a plan mode driven workflow could also be spec-as-source.

SDD in 2026

It’s hard to gain a read on where and how SDD is being used today. I have friends at Amazon that use Kiro. I have an entrepreneur friend who used spec-kit in his company and then moved off of it in favor of Claude Code Plan Mode, telling me that the spec documents were overkill.

On X, I don’t see anyone talking about SDD, but a lot of talk about Plan mode and the Ralph Wiggum loop where you define your goals granularly in a document and let Claude Code repeatedly grab one, work on it, and update the document for the next instance of the loop. X is a great way to get a pulse on AI trends, but it tends to be hype-driven and it over-represents enthusiasts, solo developers, and startups. I’m curious about how many larger teams have embraced SDD, and if a large team moves onto it, they will likely stay on it for a while.

As a solo developer, I’ve been using Plan mode, which lets me work on a spec with a lot of flexibility. I agree with my friend; I find that I don’t miss the structure or heavy markdown of spec-kit. I gave Claude some custom instructions to save the plans to a /plans folder in my repo. I also tell it to save any follow up prompts I give as I’m shaping the plan. I have occasionally re-executed a plan, which is especially helpful if you want to try it with a different model, but mostly it is a reference for understanding how something was introduced into the code.

I’ll continue to keep tabs on SDD—any new insights will be incorporated into this article.